Watching the December 19 DC council hearing on truancy and absenteeism, featuring a bevvy of government witnesses testifying over the course of 4 hours, brought to mind the parable of blind men trying to describe an elephant—in this case, the causes of, and solutions to, the high percentages of DC students chronically absent and truant as recently reported by the office of the state superintendent of education (OSSE).

Recall that this 12/19 hearing was a reconvening of one that began on December 12 with public witnesses. Recall also that the 12/12 hearing (see the witness list here and the video here) was delayed for more than 2 hours due to the council and mayor planning to quickly spirit half a billion in DC taxpayer funds to a billionaire.

Turns out, that delay was a tell.

On December 12, dozens of public witnesses testified before a minority of council members about problems behind processes, funding, and potential solutions for truancy. If you don’t want to slog through the entire 4+ hours, be sure to catch teacher Karley Sessoms’ words starting at the 3 hour 48 minute mark and starting at 4 hours 31 minutes as well as the testimony of Children’s Law Center staff starting at the 4 hour 35 minute mark.

Yet starting at the 5 hour, 11 minute mark, council chair Phil Mendelson pushed back on public witnesses who suggested a government agency like CFSA (DC’s Child and Family Services Agency) is not in the best position to help and that basic needs must be met first–which naturally entails money to address poverty head on.

When one witness (Cynthia Robbins, a self-described “concerned citizen” and co-founder of the Every Student, Every Day Coalition) noted at the 5 hour 27 minute and 50 second mark that since public money was somehow found for school police those funds could be re-directed to school social workers, Mendelson immediately pushed back, saying “no, don’t do that—that’s not one for one.”

Mendelson then went on to say, rather defensively, that mental health supports were funded this year in schools and that “the charter sector” was “cheated” of $20-$30 million (albeit without specifying what exactly charters were cheated of).

By that late hour, no government witness was going to be called to testify—including the executive director of the charter board, who was on the government witness list for the 12/12 hearing (and could, presumably, expound on how charters were “cheated”).

Thus, a week later, on December 19, that truancy and absenteeism hearing was reconvened with government witnesses. Curiously, the executive director of the charter board was absent from both the 12/19 hearing witness list and the hearing itself—with no explanation by anyone.

So it was that on December 19, a minority (again) of council members ranged from expressing “concern” (W2’s Brooke Pinto at the top) to getting into the weeds of how and when schools refer students to CFSA and court social services (about half who are eligible); how often CFSA investigates those referred to it (fewer); and how often DC’s court social services screens students referred to it (even fewer).

At the same time, council members heard repeated assurances that the system “works as designed” (deputy mayor for education Paul Kihn, at the 1 hour 17 minute and 2 hour 3 minute marks of the December 19 hearing video here) and that the numbers are “improved” (OSSE head Christina Grant, at the 26 minute mark).

To be sure, one need not listen to either the 12/12 or 12/19 hearing to know how ineffective the DC council is at being DC’s de facto school board under mayoral control. (Examples abound: see here and here and here and here for starters.)

But the official government players’ discussions on December 19 around the 43% and 37% of DC students who in SY22-23 missed 10% or more of instructional days or had 10 or more full days unexcused, respectively, more often than not sidestepped the vast plain of untold tragedies behind those numbers. Not surprisingly, nearly 3 hours into the December 19 hearing Mendelson asked the CFSA witness what that agency’s role in schools was (no clear answer)–and then almost plaintively asked, “if not you, then who?” (ditto).

Chronic absenteeism and truancy are not exactly unknown in DC. In 2017, the council held a hearing on the subject, prompted by a few well-publicized tragedies as well as longstanding, quotidian failures. Per OSSE’s newly released report, the lowest recently reported rates for chronic absenteeism and truancy in DC’s schools were in SY2015-16, at 26% and 21%, respectively. Now, after a high of 48% and 42%, respectively, in SY21-22, one can see clearly how devastating the pandemic was (and still is) on what is clearly a longstanding problem in DC.

Yet even though in the days after OSSE’s recent report came out plenty of reporting clearly outlined the issues involved (see here and here and here), the government witnesses on December 19 provided nothing new–and plenty that teetered between tragedy and inanity around causes and solutions.

Whether it was DCPS being late with data; both the DME and OSSE deferring to schools to explain why they do not refer more students for truancy (at 1 hour 56 minutes OSSE’s Grant said they want to give schools “an opportunity to explain,” which was echoed by the CFSA rep. at the 2 hour, 36 minute mark, who noted that CFSA should be involved only when there are “other things” happening); the fact that there is no auditing of LEA reporting of absences; no government witness testifying directly about the DC schools that educate 50% of DC students (yeah, that’s charters); and W2 council member Pinto going into (at the 1 hour 34 minute mark) whether the change from the 80/20 to 60/40 rule results in underreporting, it was difficult to witness 4 hours of so little consequence.

In the end, regardless of how one feels about the roles of any government agency, the tens of thousands of DC students chronically absent or truant last school year puts into stark relief the fact that in 2022, DC’s family court (specifically, CSSD, DC’s court social services division) reported screening only 239 students. (Yes: read it here on p. 79 of the family court’s latest annual report.) This number represents a decrease in screening from the prior year, which itself was a decrease from the year before that.

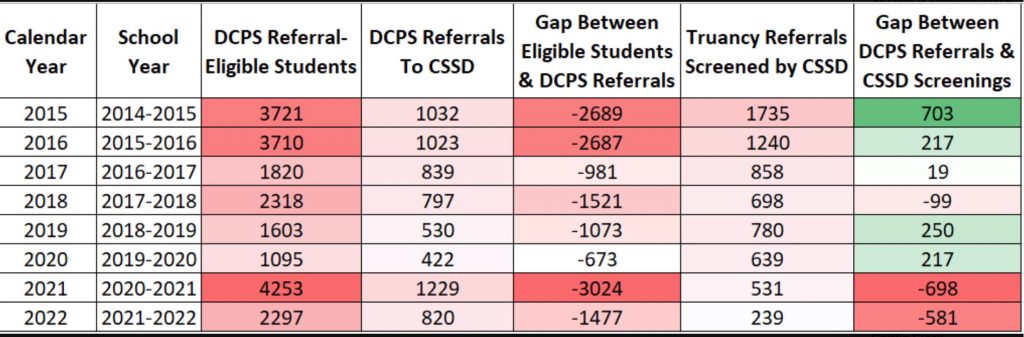

In fact, using public data sets anonymous twitter account DC Crime Facts created the helpful table below to show that this decrease in screening over time by DC’s family court suggests hundreds of absent students are literally being officially ignored every year:

Copyright 2023/24 DC Crime Facts

As bad as that is, this table doesn’t include referrals to family court from DC charter schools—which in SY22-23 numbered 726 per the SY22-23 charter attendance report. So the gap between total DC students referred and the total screened is even higher than the table above portrays.

And—sadly, unsurprisingly–the data behind all of this is not obvious.

For instance, as far as I can tell neither the annual reports of the family court (nor DC court annual reports) nor OSSE’s attendance reports show totals of students referred to CSSD annually, while the only reporting of referrals of students to that court that I was able to find was in individual annual DCPS attendance reports and individual annual charter attendance reports.

In other words, while we know that the number of students referred to court by DCPS in SY22-23 was 1138, out of a total eligible of 2572 (see p. 15 of the DCPS SY22-23 attendance report from this website), and the number referred by charters in SY22-23 was 726 (see p. 18 of the SY22-23 charter attendance report from this website), we don’t know

–the total students eligible for referral to court from charters that (or any) year;

–the totals being referred to that court annually from all our publicly funded schools except as one calculates it from individual annual DCPS and charter reports; and

–the percentage of those referrals screened by the court each year (which the table above suggests is always small).

This all is, in a word, lousy.

But in a city in which absenteeism and truancy are longstanding problems borne by our most vulnerable residents, it amounts to official dereliction. As OSSE’s recent report made clear, students with disabilities, in the care of CFSA, or those deemed at risk had the largest percentages of chronic absence and truancy in SY22-23.

In other words, poverty and all its attendant ills are at the heart of truancy and absenteeism in DC.

Yet at that December 19 hearing, I heard only one government witness who seemed to fully and correctly comprehend that elephant in the room and offer concrete strategies to deal with it. That was Nakisha Winston, a special education attorney for DC’s public defender service.

Here is Winston’s testimony, which she began delivering at the 2 hour, 7 minute, 45 second mark of the hearing video. It’s well worth perusing (and stands in stark contrast to the charter board’s airy write-up of the 12/19 hearing).

Early on, Winston notes that because “students most affected by absenteeism are students of color from economically disadvantaged homes,” racial justice demands “attendance policies must not be punitive and exclusionary, but instead should be designed to keep students in school.” Winston’s recommendations include

–Better and more accurate assessments of problems in students, with more interventions and community-based supports;

–Better understanding and remediation of barriers that students with disabilities face that increase absenteeism and truancy, including denial of needed services;

–Increased instruction possibilities for students with chronic health conditions, with parents more empowered to demand that;

–Better student supports inside and outside of schools, including more timely interventions and referrals;

–Safe spaces during the school year both in terms of time and physical space in schools for students experiencing trauma;

–Understanding how policies for pushing out students exacerbate attendance problems;

–Understanding how youth in the justice system face barriers to attendance and to attaining credit; and

–Addressing agency failures to communicate and coordinate with other agencies around truancy.

To be sure, Winston is hardly alone in understanding root causes and outlining solutions; see, for instance, another insightful local perspective as well as this one beyond DC as well as the public witness testimony at the 12/12 hearing from the Children’s Law Center here. Indeed, the DC auditor years ago proposed an early warning system at the state level, handled by OSSE and across sectors, to proactively address truancy and absenteeism—only to have it ignored.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy is that DC has ample resources to address both root causes of, and solutions for, truancy and absenteeism.

In 2023, for instance, the deputy mayor for education (DME) spent almost $500,000 on a private organization that touts its ability to reduce absenteeism by “nudging” students with reminders to attend school. Despite the DME’s positive spin on such “nudging” (see here and here) and its purported low cost (<$6/student we are told!), the end result is not exactly heartwarming. That is because “nudging” students is just that—not a long-term solution to the causes of absenteeism and truancy.

Then, too, at the 1 hour 54 minute mark of the December 19 hearing, OSSE’s Christina Grant noted that her agency is “dramatically rethinking” the “truancy packets” it spends $100,000 on every year. What, exactly, those packets have accomplished wasn’t clear—but the fact that truancy and absenteeism are still a crisis suggests that $100,000 annual cost has not been a fruitful investment.

And we should never forget the $500 MILLION in taxpayer funds that both the mayor and council chair quickly found to entice a billionaire—all the while literally delaying hearing about DC students in crisis.

In fact, at the same time the two most powerful elected officials in DC were busy waving a cool half billion at a billionaire, more than 8000 DC students were homeless—double the number in the prior decade. Not coincidentally, the value of residential real estate in DC in that time grew exponentially, as the mayor prioritized development of homes for wealthier residents.

So tell me:

How does one “nudge” a child to attend school when that child may not have a reliable place to sleep?

Did OSSE’s “truancy packets” ever offer anything toward warm shelter or a safe bed?

And how many of DC’s 8000 homeless kids could be housed for the $500 MILLION found in a period of mere hours by our two most powerful elected leaders?

While poverty is a root cause of DC’s truancy and absenteeism crisis, it is nothing next to the poverty of DC officials repeatedly turning a blind eye to it.

[Update February 24, 2024: At the end of January, at large council member Christina Henderson sent me agency responses to questions the council raised during this hearing. I have linked to the responses below, which AFAIK do not exist on the council hearings website. That is oddly fitting, as some of the responses are, for me anyway, like the proverbial riddle wrapped in an enigma.

OSSE, DCPS, and OAG responses: In this compilation of responses (put together by committee of the whole staff), OSSE answered a question about whether it publishes summaries of barriers to attendance, action plans, and services used to reduce absenteeism in schools. In its response, OSSE differentiated between DCPS and what it was calling PCSB (public charter school board), noting that it was merely quoting each sector’s attendance reports. But in the attendance report for charters, for instance, there is no way to know how prevalent any of these things are in any given LEA or what LEAs are specifically doing—and there are dozens of charter LEAs! So this is basically a nonresponse for the schools that educate about 50% of DC kids.

CSSD response: For SY22-23, CSSD says it screened 933 truancy referrals, with 799 from DCPS and 134 from DCPCS. Using the charter and DCPS attendance reports for that school year, I can see that 726 students were referred from charters, while 1138 were referred from DCPS. That means of DCPS students referred, 70% were screened while of the charter students referred, only 18% were screened. So: Why the difference? Are charters doing something differently such that CSSD cannot or will not screen referred charter students? What does this mean for the students not screened, who are overwhelmingly more likely to be from charter schools? Are the students being removed from the charters into their DCPS schools of right before the screening?? Who knows?

CFSA response: The agency was asked what happened with the approximately 6000 reports screened out last year and how many were referred to other agencies and programs. CFSA responded that it “does not capture referrals to agencies once a report is screened out. However, as a part of our process, we assess each referral. There is engagement that occurs both with the schools and the parent.” Given the answers above, that answer suggests nothing is happening—especially as student churn between schools (which we know is a huge problem for many DC students) is not tracked at all.]