[Ed. Note: What follows immediately below is a brief burying of the lede above, for context setting. If you wish, simply scroll down to the bold heading “Powerful Information To Help Advocate For Our Schools,” which has some budget resources, including a budget outline by DCPS parent and education researcher Betsy Wolf.]

Last Friday, February 24, at the tail-end of the February DCPS break, the DC Council’s committee of the whole held a re-convened hearing on initial DCPS budgets.

That is the politest thing one can say about any aspect of this process.

The original council budget hearing, on February 13, featured only two witnesses, Chancellor Ferebee and Deputy Mayor of Education (DME) Paul Kihn.

The idea of that 2/13 hearing was to outline DCPS’s initial school budgets, which were to have been released by that time per the law passed in December, which also outlined that budgets could not be cut and would be presented earlier than in prior years.

Yet instead of poring over budgets, which were not yet in existence (ergo no public witnesses, either), 7 of the 13 council members at that 2/13 hearing questioned why the law was not being followed; when the budgets would be released; how we can manage to have adequate budgets with ever-increasing numbers of schools; when we would have information about an increase in the uniform per student funding formula (UPSFF); and what the schedule is for turning the budgets in.

Good questions—but the council members did not get good answers (or sometimes any), though Chancellor Ferebee noted that principals would get advance notice of budgets as well as a head’s up on a deadline once the budgets were released.

Two days later, on February 15, DCPS released initial school budgets (well, most of them).

Despite the chancellor’s 2/13 statement, neither my DCPS school’s budget nor its deadline were shared with my school ahead of time (or really at all), with the latter changing several times.

(Fun fact: I was attending an emergency LSAT meeting shortly after the budget release, where the principal noted that no one knew what the deadline was, so I called DCPS during the meeting and was told it was March 1—with the principal’s petition deadline a week earlier, during the DCPS February break. Who knew trying dcps.schoolfunding@k12.dc.gov or 202-431-2879 would give an answer in real time?)

What quickly became very clear was that many of those DCPS initial budgets featured a wide variety of cuts. Specifically, 67 schools are slated to lose money relative to last year, with only a fraction of those schools having projected drops in enrollment.

But here’s where the 2/24 hearing comes in.

The relatively few public witnesses for that hearing (remember: DCPS was on break!) outlined devastating problems, including huge expenditures at DCPS’s central office; lack of transparency; inherent instability of budgets; basic and ongoing inequity in them; and the galling violation of the new law.

Yet after that testimony, our DME simply noted that it’s really only 44 schools getting cuts.

To be sure, that is a bit less pollyanna that the Post, which claimed only 20 schools were losing funds, per its incredible DCPS budget reporting here, which also mistakenly claimed that the weighted per pupil funding has been in place for only 1 year and accepted wholesale a charter lobbyist talking point that funds from the increase in the teachers’ union contract that may go to DC charter schools will actually be given to DC charter teachers.

Or, as the DME also put it at that 2/24 hearing, 72 DCPS schools are gaining . . . something.

As the DME went on to outline, in fact, the difference in the number of schools receiving cuts (67 versus 44) is because he and his merry band didn’t count the removal of one-time funding–pandemic recovery money–AS a loss.

(Smooth.)

The DME then helpfully noted that schools require fewer resources now anyway because covid is–well, if not rainbows, kittens, and sunshine, something a bit less than a pandemic.

At the 3 hour, 16 minute mark of the 2/24 hearing video here, council chair Phil Mendelson then began a long recitation of schools with large cuts precisely because the law was not followed:

Whitlock (formerly Aiton): 390K cut

Anacostia: 670K cut

Garfield: 156K cut

Hart: 225K cut

Hendley: 697K cut

Johnson: 521K cut

Kelly Miller: 650K cut

Ketcham: 201K cut

Martin Luther King: 162K cut

Kramer: 349K cut

Malcolm X: 264K cut

Plummer: 380K cut

Ron Brown: 582K cut

Savoy: 228K cut

Sousa: 332K cut

Stanton: 477K cut

Whether you are part of team reality or just a well-paid sophist, that list is sobering not merely because of the magnitude of the cuts, but because of where those schools are—in wards 7 and 8—and because of the students they have (mostly at risk).

The bad news naturally didn’t stop there:

Ward 3 council member Matt Frumin (who along with Mendelson was the only council member to be present at both budget hearings) worried about next year, with the effect of the pay raise for teachers next school year alongside the loss of relief money (the so-called fiscal cliff), resulting in a “dramatic” decrease in buying power.

Powerful Information To Help Advocate For Our Schools

–DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) has an excellent guide to DCPS budgets here.

–With more central office staff than ever, as DCPS budget expert Mary Levy outlines, DCPS is on track to defund schools at an almost unprecedented rate. Levy’s 2/24 testimony not only gets to that, but also outlines exactly how much schools are losing. (A spreadsheet included with her testimony is here.)

–DCFPI’s senior policy analyst Qubilah Huddleston outlines in her 2/24 testimony how DCPS’s budgeting adversely affects schools primarily in the poorest areas of the city, with many schools there also facing steep enrollment declines: “How are schools to improve if they keep losing so many students and consequently funding?”

–The head of the DCPS teachers’ union, Jacqueline Pogue Lyons, used her 2/24 testimony to outline how uncoupled the budget cuts are from enrollment, while noting that growing achievement gaps indicate greater resources are needed.

–Ward 2 ed council head David Alpert outlines in his 2/24 testimony the illegality of what DCPS is doing by ignoring the budget law—and the fundamental problems it will leave in its wake.

–Volunteers, not DCPS, have spent hours creating searchable spreadsheets of DCPS budget information for individual schools. Here are TWO excellent resources, courtesy of the following unpaid volunteers (in alphabetical order): David Alpert, Bill DeBaun, Mary Levy, and Betsy Wolf.

–Finally, below is the 2/24 testimony of DCPS parent and professional education researcher Betsy Wolf, reprinted with her permission. It outlines exactly the shortfalls in the DCPS budgeting by stripping away special education and English language learner (EL) funding, showing that the baseline funding DCPS allots is inadequate—at best.

——————————————————————-

By Betsy Wolf

DCPS dropped its FY24 budget models last week [week of February 13]. Here are some insights.

Background: Looking at per pupil budget amounts without considering context is very misleading. Example: Let’s say a school has many self-contained classes. It may look like the school has substantially more $, but that’s not actually true. Moreover, special ed and English learner dollars only reach those student subgroups, who are in the minority in the vast majority of schools.

Solution: The best way to compare budgets across schools is to first remove the $ going to special education and EL students. Removing fixed positions (including psychologists and social workers) and funding buckets for special education and EL students gives a better comparison.

Caveats: The following graphs also include federal Title I/II funds, so not all dollars are local, and I also excluded ROTC and pool costs because those are outside the education program.

Let’s look at elementary schools.

CREDIT: Betsy Wolf 2023, with data compiled by unpaid volunteers because DCPS did not provide the school budget data in spreadsheet format.

We can see that the per-pupil amount increases with the percent “at-risk” in the school, which is a good thing. For schools with similar “at-risk” percentages, FY24 enrollment also explains some differences, with lower per-pupil costs for schools with larger enrollments.

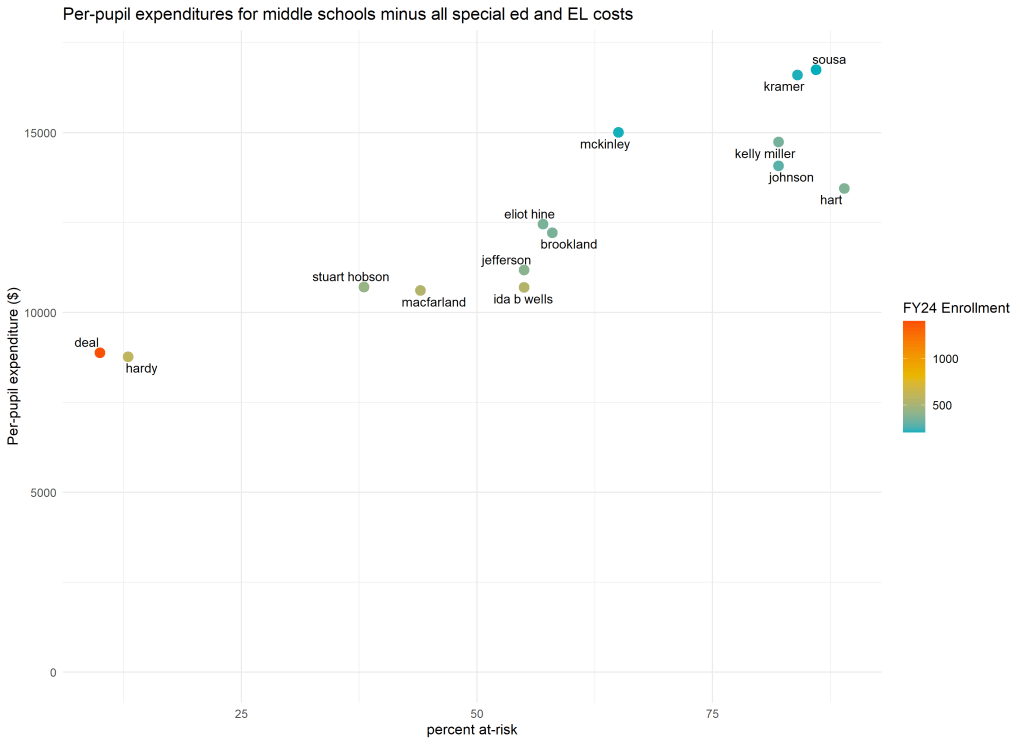

Let’s look at middle schools. Again, the per-pupil cost goes up with % “at-risk” in the school, and the per-pupil cost is higher in schools with lower enrollments.

CREDIT: Betsy Wolf 2023, with data compiled by unpaid volunteers because DCPS did not provide the school budget data in spreadsheet format.

Same findings for education campuses (elementary + middle schools).

CREDIT: Betsy Wolf 2023, with data compiled by unpaid volunteers because DCPS did not provide the school budget data in spreadsheet format.

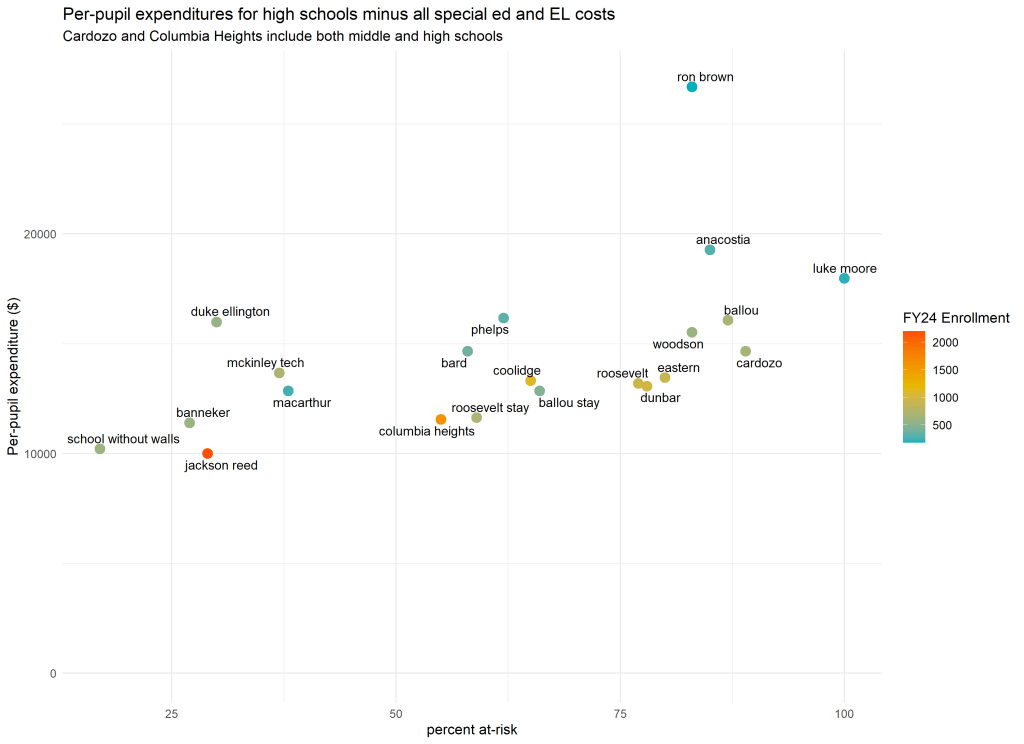

And finally for high schools:

CREDIT: Betsy Wolf 2023, with data compiled by unpaid volunteers because DCPS did not provide the school budget data in spreadsheet format.

Insights: The upward trend for higher per-pupil amounts for schools serving a higher % of students classified as “at-risk” is a promising sign for equity, but is it enough? Short answer is probably not. Researchers have estimated how much more $ students coming from underserved communities need to achieve the same outcomes as those who are not. Estimates range, but some estimates indicate double the resources (or more) is needed.

Nevertheless, equity has been improved. Take a look at a similar graph from 2017-18 for elementary schools under the former DCPS budget model where we did NOT see increases in per-pupil costs for schools serving underserved communities:

CREDIT: Betsy Wolf 2023, with data provided by Mary Levy from 2017-18.

A question not answered by these graphs is adequacy. Are the base amounts enough to cover the general education program, including grade-level teachers, minimum number of specials teachers, the assistant principal, and instructional coach? Probably not. If a hypothetical school had 2 classes in each of grades PK3-5 and an enrollment of 350, the per-pupil cost for the bare minimum school leadership and teachers would be about $10,000. Some schools are below this threshold, and this is really the bare minimum.

Schools with targeted funds can pull from their targeted funding buckets to cover basic costs (but this diminishes equity since targeted funding buckets are intended for students with additional needs), and schools without much targeted funds receive other mysterious funding buckets (like Mayor’s recovery) to cover basic costs. The bottom line is that DCPS is still supplanting funds, and DCPS needs to adequately fund the base for all schools. We can’t truly have year-to-year stability until they do this.

Another question not answered by these graphs is year-to-year stability, which is important. What DCPS budget formulas don’t address though is declining enrollments due to unrestrained openings of new schools. Should we allow schools for which students are guaranteed a seat any day of the school year to completely close in some communities? I don’t think so.

Council also recently passed legislation to achieve more year-to-year stability of DCPS school budgets. But DCPS’s previous system of school budget was neither fair nor equitable. Don’t we want stable, fair, AND equitable budgets? It was interesting to me that out of the three goals of stability, equity, and adequacy, Council has passed legislation on only one of these three goals (stability). But all are equally important.

So where do we go from here? DCPS should increase the base for all schools so that the base student-level funding covers general education costs, and schools won’t need mysterious funding buckets to fund the basics. This would help with both adequacy and year-to-year stability. We should also examine whether schools serving underserved communities are receiving enough extra funds to provide supports above and beyond what other schools are getting. Let’s also not forget about PTA/PTO funds in getting a holistic picture of what we’re spending to educate students at different schools.

Addendum: The data were compiled by unpaid volunteers because DCPS did not release school budget data in spreadsheet format. In addition, the data and graphs were not formally reviewed as they were created by volunteers, and there may be errors. This is Twitter-rigor, and the data are here: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1i3BCezzno9ATttmTAxqQxjpKSo3QnUAVEJyDgUhJ6tY/edit#gid=1099378998.

Finally, the timing of the release of the budgets was horrible, in that LSATs needed to meet to discuss the budgets, but school was closed this week [week of February 20] so many parents and LSAT members were out of town. DCPS really needs to work on the timing piece.